Good communication is just as stimulating as black coffee,

and just as hard to sleep after.

〰 Anne Morrow Lindbergh 〰

Before Words Began

Anyone can speak Troll.

All you have to do is point and grunt.

〰 J.K. Rowling 〰

“In the beginning was the Word,” so the opening statement of the New Testament, followed by “and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Word is used here not in the sense of an etymon ~ a basic unit of language, a sequence of letters associated with definitions and meaning, a building block for sentences, questions, or commands in human communication, as we know it. It is used in reference to a person, a historic and religious character called Jesus, the Son of God.

Jesus is identified as Logos (= word in Greek) ~ a divine medium of communication between God and humanity.

Tracking the term word itself back to the old Germanic wurða (= to speak, say), it is impossible to determine since when it was used by our ancestral English speakers.

What we do know is that the contemporary English word is cognate with the German Wort = expression, statement, word, answer, saying, quote, sentence, proverb, motto, agreement, vote, spell, password, signal, remark, comment, message, notice, sentence, promise, verbal exchange, brief communication.

It has most likely been around since ancient times. Find further glimpses into the history of word in my earlier wordcast The Wild Motherword.

Although words have been firmly associated with language for millennia, we must keep in mind that words ~ whether written or spoken ~ do not mark the beginnings of human communication.

Or, to look at it from another angle: If we define language as a form of human communication, it most certainly did not start with words. Researchers into this field of human evolution suggest that the development of human communication went something like this:

1st › vocal expressions to convey warnings or emotions, describe experiences, or offer social cues, presumably in pure sounds such as calling, crying, growling, grunting, hissing, laughing, screaming, shouting, shrieking, or any other type of non-verbal vocalisation

2nd ›› gestures, grimaces, and body language with hand signs, such as pointing, poking, waving, touching body parts etc.

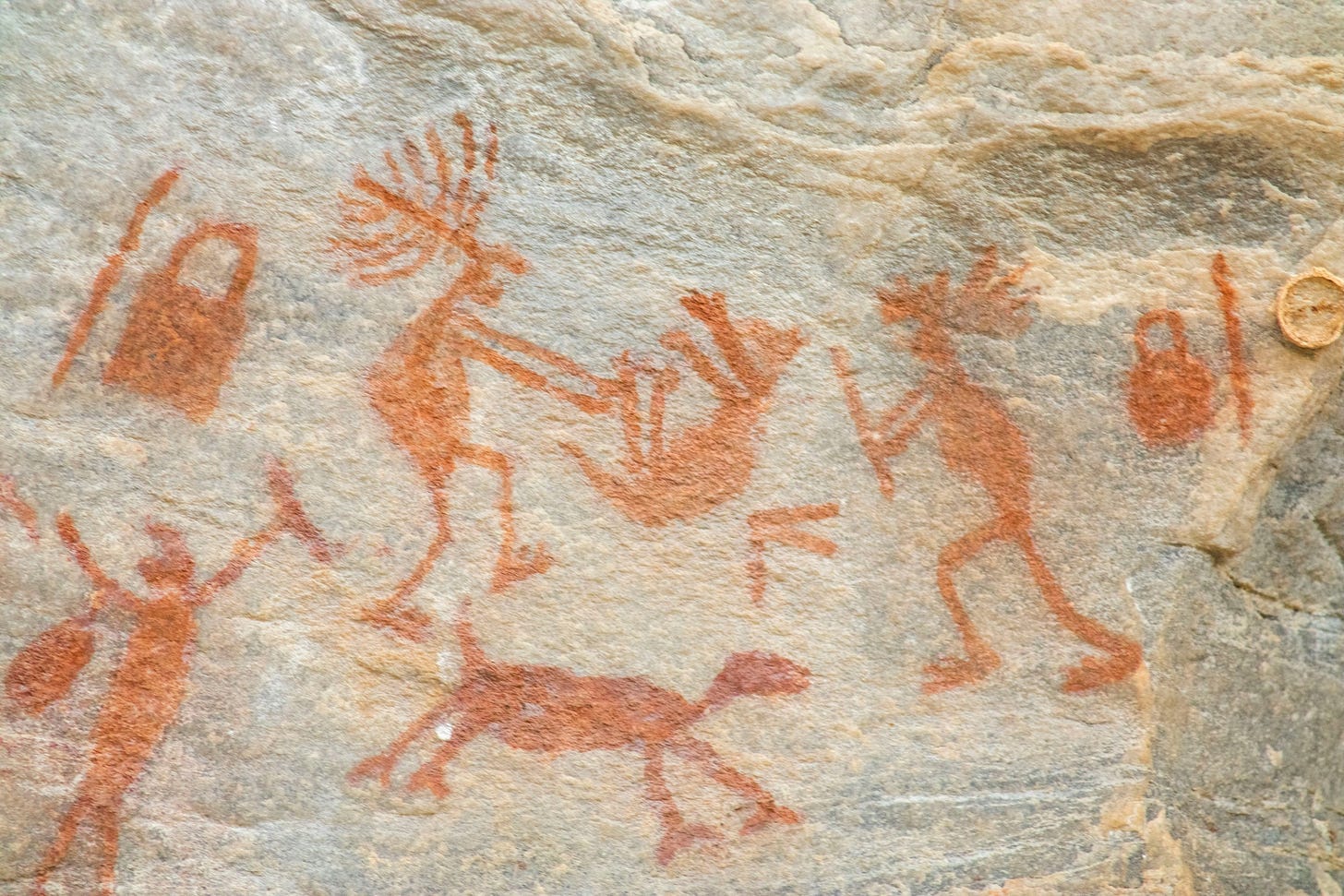

3rd ››› symbolic communication through petroglyphs (rock carving) and pictograms (line drawings) ~ the oldest forms of symbolic expressions in cave paintings and etching date back to around 30,000 BC

4th ›››› images and visual representations of events to share experiences, preserved in cave paintings (often of hunts, battles, or rituals)

5th ››››› oral traditions in rituals, ceremonies, and storytelling

6th ›››››› poetry and performances in music, dance, and acting

7th ››››››› early writing systems in cuneiform signs and hieroglyphs from 3300 BCE in Mesopotamia and Egypt

How to Kill Dirty Language

They thought it was a language of savages and not created by God.

〰 Theodore Fontaine 〰

Some years ago, after befriending a mother with two children, I witnessed an unsettling incident. She threatened to wash her child’s mouth for ‘using dirty language.’

Shortly after learning about this peculiar disciplinary threat (or action), I read that washing children’s mouth with soap had been a common punishment in so-called ‘Residential Schools’ set up by colonialists in Canada and America for the indigenous population. The children were not allowed to speak in their native language.

“I was startled when Sister S., the supervisor that day, almost knocked me on my back as she wrapped her powerful, bony arm around mine. I’d inadvertently said something in Ojibway,” Theodore Fontaine recalls in his memoir Broken Circle. “She’d assumed I was referring to her when a couple of the boys laughed at my comment. She yelled that she’d wash out my mouth with soap.”

Colonialist missionaries on the American and Australian continents perceived indigenous languages as inferior, savage, or daemonic ~ assessments which justified, in their minds, the eradication of the native tongues. Indian Residential Schools, were established under the motto of ‘Kill the Indian, save the man.’

The policy of suppressing certain languages and dialects, however, was not unprecedented. Here are some examples from European history and beyond:

In 1366 the first English law banning the use of the Irish language is enacted as ‘Article III of the Statute of Kilkenny’.

In 1492 Antonio de Nebrija writes the first grammar of the Spanish Castilian language, noting in a letter to Queen Isabella I, “After Your Highness has subjected barbarous peoples and nations of varied tongues, with conquest will come the need for them to accept the laws that the conqueror imposes on the conquered, and among them our language.”

In 1535 the Laws in Wales Act decrees that English is the only language to be used in Welsh courts. Destructive policies follow, aiming to eradicate the Welsh language. (This law was repealed by the Welsh Language Act only in 1993)

In 1697 under Peter the Great in Russia, Belarusian loses its status as an official language and is banned from all state and court documents.

In 1757 the King of Portugal bans the indigenous Tupinambá language in colonized Brazil.

In 1770 King Carlos III of Spain issues a decree that prohibits the use of Indigenous languages in all colonies of Spain.

In the second half of the 19th century, speakers of languages other than German are labeled as Reichsfeinde (= foes of the Prussian empire).

In 1851 Norway forces Sámi schools by law to teach in Norwegian.

In 1868 Ezo Island is annexed by Japan and renamed Hokkaido. Japanese settlers force the native Ainu population to attend Japanese schools and ban their language.

In 1880, the 2nd International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Milan issues a declaration that oral education is superior to manual education and passes a resolution to ban sign language in many European countries and the US.

This incomplete list of cases of linguicide ~ the death of languages alongside genocide ~ has an unsettling global history.

Linguicide is either provoked directly by systematic annihilation, massacres of whole populations, separation of children from their families, wars and violent suppression of certain cultures, or more indirectly through the spread of infectious diseases, starvation, and the cultivation of inequality and discrimination.

Language: the Song of the Taste Organ

Touch comes before sight, before speech.

It is the first language and the last,

and it always tells the truth.

〰 Margaret Atwood 〰

The term langue (= language) was adopted in French from the Latin lingua (= tongue; speech, language; tongue of land). The French langue was already firmly established in the Old French period (9th–14th centuries) and used with the same meanings of the Latin lingua.

The forerunner of language was introduced into English in late 13 c. in the French form langage, in the sense of words, manner of expression, conversation, talk.

The contemporary word language developed from the French form, originally defined as “The whole body of uttered signs employed and understood by a given community as expressions of its thoughts; the aggregate of words, and of methods of their combination into sentences, used in a community for communication and record and for carrying on the processes of thought.” (Century Dictionary, 1897)

Tongue [Old English tunge = tongue, organ of speech] arrived in English via the Old High German zunga, from the Old Norse tunga before the 12th c. It was defined as the ‘lingual apparatus and principal organ of taste’ while being applied in English in the sense of speech, faculty of speech, a people’s language, and especially in the context of foreign tongues from early on.

Both, the Nordic word tunga and the Latin root word lingua were used in the sense of the anatomical tongue; the phenomenon of human language; and a narrow headland shaped like a tongue and sticking out into the sea.

Not surprisingly, tongue and language became partial synonyms and can be used interchangeably in certain contexts. The uses of both terms are so familiar that the use of the word tongue as a metaphor for language almost goes unnoticed.

Meanwhile, the Latin root word lingua is also responsible for the related terms bilingual, lingo, linguist, multilingual, etc., establishing itself firmly in our linguistic terminology.

Despite the fact that the tongue is only one of several essential organs for the development, pronunciation, and articulation of human speech, the word stuck. Language in general, as well as mother tongue and foreign languages, became inseparably associated with the muscular organ, attached to the back of the cavity of the mouth ~ which primarily fulfills several vital roles to enable us to taste, eat, swallow ~ while assisting in the process of producing the body of words we associate with verbal expression.

Every language swallows certain words. English is good at eating auxiliary verbs:

I am becomes I’m

You would becomes you’d

We have becomes we’ve

He has becomes he’s

She will becomes she’ll etc.

Streams of words and word-fragments flow from billions of human tongues ~ performed as on-demand and mostly improvised gigs in over 7000 languages ~ with hardly any attention paid to the miraculous oral performance of what

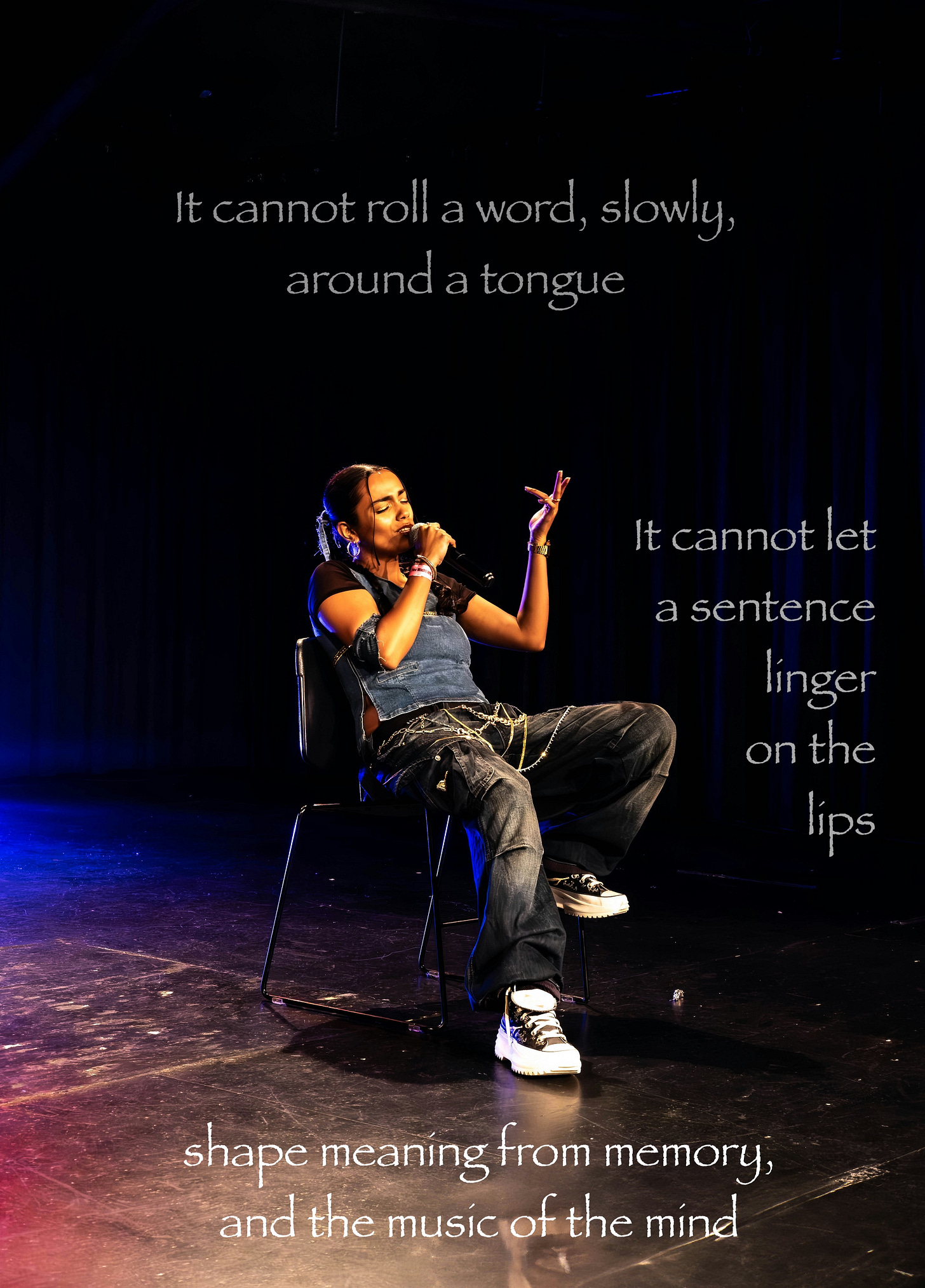

calls ‘the music of the mind’.In her recent posting AI cannot do this Emily has taken a closer look at the interaction between tongue and language and shares her perceptive observations, while reminding us of the gifts of human languaging:

»It cannot roll a word, slowly, around a tongue, in a mouth full of teeth, feel the pull of muscles shaping phrases to reverberate in a larynx, or taste the weight of syllables balanced on a breath. It cannot feel the rising swell of a vowel, nor the catch of a consonant at the back of the throat. It cannot let a sentence linger on the lips, shape meaning from memory, and the music of the mind.«

Ah Veronika! Words! The synchronicity to my current writing is now being referred to as a soulchronicity!

Words. Giving language to words -

Words to language. The first sound is no sound. A naked indentation. The tip of a word on a taste of tongue. Touched. Lips. Tasted. Imagination. Heard. Nosed. Before it’s scent is released as anything visual. Its beyond eyes.

“AI cannot roll a word, slowly, around a tongue, in a mouth full of teeth, feel the pull of muscles shaping phrases to reverberate in a larynx, or taste the weight of syllables balanced on a breath. It cannot feel the rising swell of a vowel, nor the catch of a consonant at the back of the throat. It cannot let a sentence linger on the lips, shape meaning from memory, and the music of the mind.”

Goosebumps! Will swallow this one slow. Words. Never to waste. Always to savour. If only to get to the other side of what words can never say to all the phases of the moon.

Keep writing! We need you! 🙏❤️

Hi Veronika,

And does the music of the mind sing the universal song of the soul — just a question that popped in for me, contextual of course. And how does that translate to our ‘tongue – language’ — landscapes and soundscapes. Thank you for bringing attention to the interchangeability here; I am always eager to sit with your offerings with language.

“we must keep in mind that words ~ whether written or spoken ~ do not mark the beginnings of human communication.”

To colonisation and linguicide; “Colonialist missionaries on the American and Australian continents perceived indigenous languages as inferior, savage, or daemonic ~ assessments which justified, in their minds, the eradication of the native tongues.”

Aboriginal Australia: over 200 languages and 800 dialects — so many lost, and as the federal election looms this weekend, we have the sickening posturing from one of the major political parties to ‘do away with welcome country’. Language is culture.

And appalling policies (currently enacted ) in some schools banning NESB students speaking L1 in classrooms. Same fear. More lost opportunities of connection and the strengthening of community.

Might we also listen to the language of the rest of the sentient beings on this planet?

Thank you for everything you offer us, and for alerting us to Emily’s post. 🙏 🌱 💜