Why do you want to persecute yourself with the question

of where all this is coming from and where it is going?

〰 Rainer Maria Rilke 〰

What is a Question?

Research is formalized curiosity.

It is prying and poking with a purpose.

〰 Zora Neale Hurston 〰

Not all questions are made equal. There are big questions and existential questions, exam-, interview-, and test-questions, and then there are trick questions, such as this one:: what can be given and broken but never held?*

The word ‘question’ can relate to circumstances, conditions, limitations, or qualifications, such as:

A question of time or a question of space?

A question of guilt, age, or gender?

A question of strength, purpose, or discipline?

A question of knowledge, education, money, means, resources, independence or dependants, family, ancestry, offspring or culture, of diplomacy, habits, intention, responsibility or priority, of authority or anonymity, perspective or loyalty, tact or taste, talent or waste?

Then there are all sorts of things you can do with a question, apart from the obvious ~ to ask:

A question to enquire, request, explore, or investigate, to check out, survey, probe, scan, scrutinise, to scout or search, inspect or research, to study and analyse, sift and examine, or consider and audit?

A question to fret, mull, obsess or brood over?

A question to speculate, opine, ruminate or kick about?

A question to solve or one to reject?

A question to die for or one to live into?

The list could go on forever… and these are just starter questions. They don’t even begin to reveal anything about the format ~ which would be the body of a question ~ or ask about content, which is ultimately the beating heart of any question.

How can it be that all of these are known by a single word with the same sound

|ˈkwɛstʃ(ə)n |?

The question What is a question? begs a whole flood of follow-up questions. Defining a Q is not as simple and straightforward as you might think.

Writers behind a website called Testfellow.com, have made an attempt at distilling this overwhelming mass of Qs into the following essence:::

“At their core, questions are the keys that unlock the doors to knowledge and discovery.”

At superficial glance, this definition sounds plausible. Closer inspection soon shows that the net cast by this description only catches a limited type of Qs, letting many others slip through the gaps.

In the past, it would have been relatively safe to say that a spoken question can be recognised by the sound of the speaker’s voice. Since the mode of speaking has changed, the explanation, ‘a question is a statement where the intonation rises at the end’ doesn’t apply anymore.

Perhaps we can stick with the grammarian answer: A question is an interrogative sentence?

Hmmm, that doesn’t quite fit either. A Q can totally work as a Q without fulfilling the grammatical requirements of being a sentence.

Any more questions?

Questions of Definition and Time

If we would have new knowledge, we must get a whole world of new questions.

〰 Susanne K. Langer 〰

Some questions are phrases asking for a response. Others are commands ordering obedience and demanding specific action. Some can be requests for information. Others may be testing particular facts, knowledge, or accuracy of certain factors.

Trick questions, like the one above are also known as riddles. Such questions don’t look for an answer but a solution. (*Btw, the solution to the above riddle is a promise.)

Most questions are open-ended statements requesting completion…, but not all.

Question [from Latin quærere = to ask seek] was adopted into English in early 13 c. in a wide range of meanings, initially as a noun: seeking, questioning, inquiry, examination, judicial investigation; verbal contention, debate; legal proceedings, litigation, accusation.

A question can also be a doubt, controversy, dispute, philosophical problem, or a trial. The word has been used for examination by torture, or the application of torture to prisoners in order to extort confession.

In Shakespeare’s era, question was used in the sense of conversation, speech, talk ~

Example: “I met the duke yesterday and had much question with him.”

In the phrase, to call into question, the word is used as a synonym for challenge.

Out of the question indicates the speaker’s unwillingness to consider a certain topic or option.

To pop the question translates into expressing the wish to marry someone.

The verb question wasn’t used in English until 15 c. Since then it has been employed as ways to ask, inquire, challenge, dispute, doubt, debate, reason, consider, examine, test, probe, express suspicion, talk, converse, call into question, express uncertainty, demand information, investigate with the intention to gain certainty, explore, contemplate, ponder, review, suspect, negate, besiege, object, censure, distrust, argue, contest, fight, resist, reject, hound, poll, quiz, hassle, annoy, or pick someone’s brains.

Before question was adopted as an English verb, the Old English ascian described the action of ‘asking, calling for an answer; making a request.’

To ask [from old high German eiscôn = to desire, covet, seek] was used alongside fregnan and frignan in the sense of question, inquire.

Simultaneous with the verb to question, the synonym to interrogate appeared in the English treasury of words. This verb is a back-formation from the noun interrogation, which describes the process of questioning and includes a whole set of questions.

The Latin word roga ~ literally stretching out the hand, the root for rogare [= to ask, propose a law] , has sprouted a whole family of English words, including:

Abrogate ~ abolish by authoritative order

Arrogant ~ assuming, overbearing, insolent (presumably from requesting more than one’s fair share)

Derogate ~ take away, diminish

Interrogate (v) [from Latin inter = between + rogare = to ask] ~ ask, inquire, cross-examine, question

Prerogative ~ special right or privilege

Prorogue ~ to ask publicly

Regent ~ ruler, governor, literally someone who has special rights to request things from others

Rogation ~ request, questioning, proposition, asking a favour

Surrogate ~ a substitute, person appointed to act for another

The now obsolete English words fregnan and frignan are cognate with the German noun Frage (= question) and the verb fragen (= to ask). All four terms ask, fregnan, question, and rogate carry an original sense of seeking, reaching out, listening out for, exploring, aspiring, striving for, searching.

We could therefore say that questions are, by nature, verbal expressions which reach out, demanding to find something ~ an answer, fulfilment, response, or solution.

Questions to Die for

I was asking questions which nobody else had asked before.

〰 Benoit Mandelbrot 〰

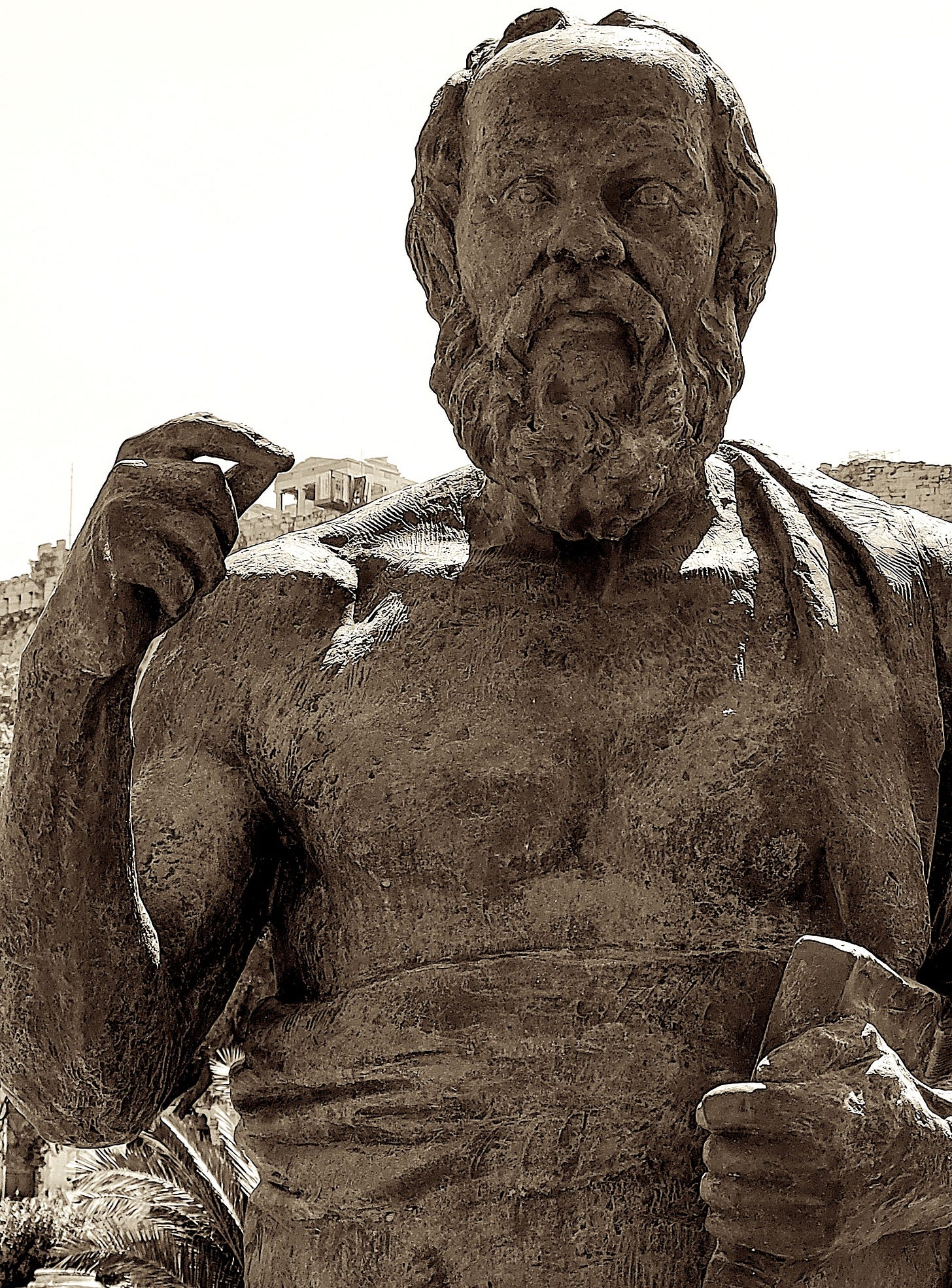

When Socrates declared that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’ he literally claimed his right to ask certain quintessential questions, even if they were considered illegal, or ‘heretic’. Three questions now known as ‘the Socratic questions’ are:

What is knowledge?

What is virtue?

What is the meaning of life?

Such essential/ existential questions allegedly raised significant suspicion, leading to serious accusations by some members of the Greek ruling classes, and ended with the tragic death sentence by poison hemlock.

Of course, it wasn’t just the questions. Socrates was accused of heresy. He most likely attracted the wrath of his enemies through his provocative behaviour, free spirit, and defiant nature.

Socrates understood the importance of learning to ask the right questions. He taught his students by encouraging them to ask their own questions, and boldly stated that, “No one can teach, if by teaching we mean the transmission of knowledge, in any mechanical fashion, from one person to another. The most that can be done is that one person who is more knowledgeable than another can, by asking a series of questions, stimulate the other to think, and so cause him to learn for himself.”

His untimely death has assured him a leading position on the olympic podium of Ancient Greek philosophers, and the name Socrates is forever associated with existential questions, which are, according his famous last words, worth dying for.

Questions to Live into

There are no right answers to wrong questions.

〰 Ursula Le Guin 〰

From 1902-1908 ~ about 2300 years after the life of Socrates was cut short ~ the Bohemian poet Rainer Maria Rilke corresponded with a young army cadet named Franz Xaver Kappus. The nineteen year old student at the Austrian military academy which Rilke had attended over a decade earlier, sought advice from the famous alumnus-turned-poet, sent him an excerpt from his own work and confessed to aspirations and doubts whether to make a similar switch and follow a more creative career path.

In 1929, Letters to a Young Poet were published, three years after Rilke’s death. The original edition contains almost exclusively Rilke’s part of the correspondence. (Due to the enduring popularity of the slim volume, Kappus’ letters were later included in new editions.)

The original edition of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet contains ten letters, which revolve mainly around questions. Rilke’s responses to the unpublished questions of Kappus consistently avoid answering the requests of his correspondence partner.

Instead of giving the young man what he wants, Rilke questions the nature of the questions themselves, and replies by asking bigger questions, such as::

What kind of questions are worth asking? and

What is the right way to go about such questions?

“You ask whether your verses are any good.” Rilke writes. “You ask me. You have asked others before this…. I beg you to stop doing that sort of thing.”

Kappus’ unpublished questions to which Rilke is referring are not essential questions. They are neither to die for nor to live into. They are requests of an aspiring young poet looking for validation and reassurance. Rilke draws a clear line of distinction between such ‘unanswerable questions’ and a deeper existential line of inquiry.

In this second category, Rilke’s response, although more appreciative of the questions themselves, is equally cautious, still warning against looking for external answers.

“The questions of love, even more than everything else that is important, cannot be resolved publicly and according to this or that agreement; that they are questions, intimate questions from one human being to another, which in any case require a new, special, wholly personal answer.”

Rilke effectively tells the young Kappus that the topics he’s asking about are inappropriate. He cannot give ‘right answers to the wrong questions’, so he throws new questions back at him.

In summary, the Letters to a Young Poet circle around questions of a 19-24 year old (the correspondence stretched over a period of six years) seeking answers about life, and a slightly older and much wiser man telling him that he is asking the wrong questions, because he’s looking in the wrong direction.

“You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you — no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.”

There is not a single phrase to kindle false hopes. Rilke offers the advice to turn inwards, to find personal idiosyncratic answers in ‘the very depths of your heart’. Instead of positive affirmations, a motivational pep-talk, or encouragement, he confronts Kappus with a direct, and possibly unsettling counter-question of three words.

Must I write?

“This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write?”

Which leaves us with the bonus question: What kept the correspondence going for six years?

My guess is that it was Rilke’s compassionate and inspiring writing style. The exchange carried on, despite the refusal to feed the young poet’s cravings with sweet talk. Or maybe because of it?

It was probably the combination of all three ~ candid honesty, empathic resonating with the desperate search for the purpose of life, and Rilke’s brilliance as a writer.

“Have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Kappus followed Rilke’s advice. He did live his way into the answer. You can find it in the introduction to the famous slim volume, right at the end. It is, as far as I know, the only text ever published by the young poet himself, “… When a great and exceptional man speaks, the insignificant must be silent.”

Thank you @Tim Burns for flicking the question pebbles across the cyber pond and making them ripple further. I truly appreciate your continued support 🙏 💕

Thank you so much, @Kameron Primm for being the wind under the wings of the Living Questions 🌍 🙏 💙