Extreme fear can neither fight nor fly

〰 William Shakespeare 〰

Fear as a Travel Companion

Now is the time to understand more so that we may fear less.

〰 Marie Curie 〰

The act of fearing as we know it today is a subjective inner experience. You can fear that something might happen. I might fear a bully launching an attack.

We can fear that, fear to, fear of, and fear for. But we can’t fear someone as in making them afraid.

This wasn’t always the case. The English verb to fear was born as an aggressive action word. About 600 years ago, to fear a person would have been understood as frightening someone, or scaring the shit out of them.

Since late 14 c. the transitive sense of driving fear into someone has given way to the now familiar meaning of being flooded with an emotional sense of fear.

Fear, verb [from Old English fǣran = to terrify, frighten] is related to Old Saxon fāron = to lie in wait, Old High German fārēn = to plot against, Old Norse færa = to taunt.

This original sense might explain why so many people are afraid of their own fear. Despite its modern use, fear still seems to have the effect of scaring us.

Fear of one’s own emotions is very common, as mentioned in my recent wordcast Unidentified Griefcases. Fear of fear itself, claims a unique position in the ‘geological upheavals’ of the inner human landscape.

This emotional wave of fear can rise when we meet fear within the inner world, without understanding where it comes from. Fear of fear is closely related to fear of the far, fear of the unknown, fear of uncertainty, fear of unpredictability etc. which may arise when stepping out of your comfort zone ~ when faring far and further from what you know.

Fare [from Old English fær = journey, road, passage, expedition] from faran = to journey, related to faru = travel, companions, baggage.

Leftovers in contemporary English linger in wayfarer, seafarer, thoroughfare, welfare. The contemporary use of the noun fare, in the sense of payment for passage, has been recorded since 1510s.

The verb to fare, is cognate with the German verb fahren (= to travel, drive, ride), which in turn is related to the German noun Gefahr (= danger, hazard, threat, risk).

Here the journey of fare bumps into fear. Travelling increases the risk of meeting with dangers lurking in a dark undergrowth.

Hunting Wild Beasts

Life begins at the end of your comfort zone.

〰 Neale Donald Walsh 〰

Gefahr referred originally to a specific type of danger ~ the peril of falling prey to an enemy, whether hostile human or wild beast. Accordingly Gefahr was associated with hunting accidents, being assaulted and robbed while travelling through wild territory, or travelling (= fahren) in general.

What etymonline doesn’t mention, is that the German Gefahr was originally called Fahr (until the 18th century). Fahr used to carry the full spectrum of meanings of the contemporary Gefahr (= danger, hazard, menace, peril, jeopardy, risk, threat).

The prefix ge- (= a collective prefix) implies that the danger, threat, or risk is not ‘just’ a personal one-off situation. Not ‘just’ a subjective impression. But a ‘real’ objective danger. The collective Gefahr was presumably introduced to distinguish between Fahrt (= faring, the act and process of travelling) and the associated perils.

In the late 19th century, the English language adopted a foreign word for a special kind of hunting adventure from Swahili, an African language with roots in Arabic soil.

Safari [from Arabic safara سفر = to travel] came into English in the sense of expedition through the African bush with the intention to hunt wild animals, especially beasts of prey.

The original Arabic root safar is the motherword not only of travel, traveller, messenger, embassy, ambassador, passenger and visitor, but also for the verbs to shine, glow, radiate, remove the veil.

The association with hunting wild animals in Africa was cast by inventing the concept of safari for a wealthy European market. By the late 1700s many of the hunted wild animals were on the verge of extinction.

Due to the efforts of 19th century etymologists to plant an ‘indogermanic language tree’, pruning away all roots from semitic languages, it is difficult to confirm, whether the word safari is etymologically related to European words such as fare and fahren.

However, one Arabic word for flight (in the sense of running away) is farra فر. [That it is made up of the same two consonants as fear and fare may be pure coincidence].

Farra فر means to flee, run away, escape, drive someone away [= to fare far driven by fear]. Farra also means to glow, shimmer, indicating its close relationship with safara سفر.

In other words, the phonetic resemblance between the Arabic farra ~ constructed of the consonants f and r ~ and the English fare/ fear, related to German Fahr = danger) is striking, to say the least.

Barr [ بر the Arabic word for mainland, or land as opposed to sea] is cognate with the Hittite word para, which is etymologically related to the English far (according to our current official etymology).

Barra is the common term for outside in colloquial Arabic. It can also be used as a command: barra! = get out!

Here the similarities with the Portuguese fora (= outside) and its Spanish equivalent fuera [both from Latin foris = outside] give a significant clue.

Afore [from Latin foris] is where we experience ourselves when stepping out of our comfort zone and travel into foreign territory.

Foreign [from Latin foris] is literally what happens outside our front door and is perceived as alien or strange and therefore potentially scary.

Forest [from Latin foris] is a dark woodland where danger potentially lurks in the undergrowth.

Forum [from Latin foris] is originally an outdoor place of assembly in Ancient Rome, used for example as a court of justice.

Forensic [from Latin foris] describes legal debates held for example at a forum.

Para- [from Latin para = defense, protection against] is used in English in words like parachute, parapet, and parasol ~ protective equipment made for different kinds of impending danger.

Para- [from Greek para = beyond, irregular, abnormal, against] is used in English words like Paralympics, paralysis, paranormal, describing situations ‘outside the ordinary.’

That fear is historically associated with (a) being far from one’s usual range of experience, (b) dark forests where wild predators roam, (c) foreign people who speak in a foreign language and behave in foreign ways, (d) forensic debates, (e) anything related to paranormal, and worst of all (f) warfare is wellknown.

That the semantic and phonetic connections between fear, fare, far, foreign, forest etc. require some forensic sleuthing is surprising enough. But the wild trail of fear through the linguistic undergrowth doesn’t end there.

The further we step beyond our comfort zone, the more vulnerable we may feel, the more susceptible to unexpected attacks, and the less prepared to handle unknown threats and dangers.

Let’s fare down another trail beyond the etymological comfort zone ~ together ~ ready to brave some seriously wild words.

Fearing the Inner Beast

Our biggest fear is taking the risk to be alive and express what we really are.

〰 Don Miguel Ruiz 〰

According to etymological theories, fear comes “from PIE *pēr-, a lengthened form of the verbal root *per- (3) ‘to try, risk.’”

Note the number (3) behind *per. On browsing the etymological dictionary, you soon find not only 1 or 3 but 5 (FIVE) hypothetical Proto-Indo-European roots called *per.

Each *per comes with its own long list of associated words. The lists have been organised, no doubt, based on diligent research, looking at word meanings in many languages, and weighing up arguments for and against each category.

An interesting detail is the relationship between the meanings mentioned under the allegedly ‘different’ *per-s.

*per (1) = forward, before, chief, in front

*per (2) = to lead, pass over, forward, through, in front of

*per (3) = to try, risk, experiment, extended root of *per (1) forward, to lead across, press forward

*per (4) = to strike, an extended sense of *per (1) forward, imprint, pregnant etc.

*per (5) = to traffic, to sell, hand over, distribute, extended sense of *per (1) forward, etc.

In other words, all these five per-categories are outcrops of the same language shrubbery. Sorting them into the different word groups listed above is fairly arbitrary, based on the intuition of the etymologist.

From the root of the hypothetically chosen *per (which could as well have been called *far, or *barr) many English words have been grafted onto the five shoots.

Fear appears under *per (3) along with experience, experiment, peril and pirate…

Fare is classified as *per (2) alongside, export, ferry, passport, port, transport, warfare, wayfarer and welfare…

Far belongs to *per (1) next to first, for, forefather, para-, paradise, percent, perfect, primary, prince, principle, protein, protest, protocol and many more

*per (4) has given us depression, espresso, impress, pregnant and anything else to do with press and print.

*per (5) is the most transactional of the five *per-roots ~ it contributes praise, precious, price, and pornography [from Greek porne = prostitute, originally meaning ‘bought, purchased’] to the *per-tree of words.

Feral [from Latin ferus = wild, uncultivated] was adopted around 1600 c. in English in the sense of ‘untamed, run wild, escaped from domestication’ and has not been grafted onto the official *per-word-shrubbery.

However, the Latin ferō [from present infinitive ferre = to bear, carry] means to carry an offspring, to be with child, to be pregnant (see *per (4)).

Latin fertus [past participle of ferō] means fertile, productive.

Latin ferox = wild, undomesticated, untamed is composed of ferō + the suffix -ox = full of, characterised by.

In the English etymological dictionary fertile has the hypothetical root *bher (1) ~ which has also allegedly sprouted bear (in the sense of carry) and birth ~ while pregnant is attributed to *per (4).

Feral [from Latin ferre = to bear + -ox = full of, characterised by] means the same as the original Latin ferox.

Interestingly, Georges Latin-German dictionary (1913-1918) differentiates between ferōcitās as courage that is caused by a feeling of inner strength and ferōcia translated as an innate quality of character.

Ferocitas is derived from ferox and has been adopted in English as ferocity (noun) and the adjective ferocious, in the sense of savagely fierce, exhibiting unrestrained violence.

Ferocious [from Latin ferus + -ox = full of] and was used in Middle English in the sense of dangerous, destructive, which links back to peril and Gefahr.

Note also, the Arabic word form barri = wild, free living species of plants and animals, flora and fauna of wild land.

This wild little excursion may show how fear, feral and peril are intimately entwined, fertilising each other, in human language as in our daily experience.

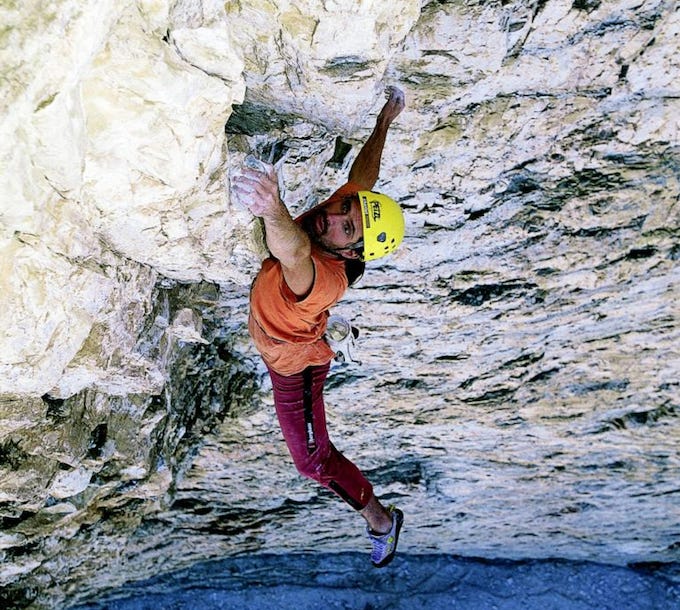

The German alpinist Alexander Huber is intimately acquainted with the ferocity of the alpine wilderness and the inner wilderness of his own fear.

Alexander Huber (rock climber, physicist, and fully trained mountain guide) was born in 1968 in a small town in Bavaria in the foothills of the Alps. When he went on his first climbing tour with his father and brother, meeting the monumental mountains face to face at the tender age of 9, it was love at first sight ~ and the beginning of an epic career.

Alexander Huber and his older brother Thomas both followed their calling to explore the highest mountains of the world. They became pioneers in a new discipline of sport, conquering the most challenging rock faces, creating new routes that had never been touched by human foot or hand.

Alexander rose to fame with his ‘free solo’ climbs. Free soloing ~ one of the most challenging, dangerous, and fearsome types of sport ~ is a form of climbing where the alpinist faces the sheer rock on his own without safety gear!

Free soloists climb above safe heights. The slightest error or accident would end fatal. You are basically on your own, stuck on a vertical or overhanging rock face.

In 2013 ~ 36 years after falling in love with the rock face ~ Alexander Huber published his book Die Angst, dein bester Freund (Fear, Your Best Friend).

From being ~ or appearing ~utterly fearless, Alexander crashed into a crevice of paralysis by fear. The devastating experience of a mental health crisis, of not knowing whether he would ever be able to climb again, transformed his perspective on life.

Meeting sheer fear in the same manner he’d faced precipitous surfaces and protuberances of the world’s highest peaks, Alexander came to understand and accept fear as his most trusted climbing companion.

It is never the mountain you conquer, but it’s always the own Self anyway.

〰 Alexander Huber 〰

In response to the quote “Extreme fear can neither fight nor fly.” by William Shakespeare, one reader of this wordcast pointed out alternative reactions to fear ~ 'freeze, flock, fawn' ~ and hinted at "other F-words"...

I was familiar with 'freeze and fawn'.

'Flock' is a brilliant one too!

Anyone knows any other F-words as fear-reactions?

Maybe 'feign and fake'?

Great one, Veronika! 🙏❤️This resonates with what I’m writing about these days: the witch archetype, our fear of women’s rage, how we push it into the underground cave of our collective unconscious and resurface, bubbles up in distorted ways.

This post really makes you think about how deeply fear is wired into us—like it’s part of our survival blueprint. It’s wild to imagine that “fear” once meant actively scaring someone, like an aggressive force, and now it’s more about what rises up within us. When you look at words like fear, fare, foreign, and forest, they all carry a sense of venturing out, risking something, leaving safe ground, and facing the unknown. It’s got me reflecting on fear in so many nuanced ways now.

Maybe that’s why fear feels like an ancient shadow, especially when we step into something new. But if we see fear as part of the journey, not just a warning—almost like "stress", which can lift us up rather than push us down—then maybe it’s a sign of growth, a push beyond old limits. Just like “fare” and “far” were about moving forward, maybe fear is a call to courage, nudging us toward a life beyond the comfort zone.

Thank you for your fearless writing and brave explorations; it’s truly inspiring. Here’s to letting fear move us forward, not hold us back—and to exploring those “seriously wild words” in our own lives. Happy weekend!